Review of ‘RIFTS’ at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre

Multiplicities of contemporary artistic practices in Thailand

By Ho See Wah

Rirkrit Tiravanija, ‘untitled (2004), jed sian samurai 2019’, 2019, 7 gas burners, 7 pots, bowls, ingredients, cooking equipment and utensils, mats, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of BACC.

‘RIFTS: Thai contemporary artistic practices in transition, 1980s – 2000s’, which opened on 30 August 2019 at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) explores an era where Thai artists were challenging normative standards. This manifested in the radical ideas presented, the wide-ranging and unconventional media used, and the interrogation of the institution of art itself.

It is not surprising that such works were created during this era. The artists grew up in a time where the Vietnam War caused a rapid “modernisation” and Westernisation of Thai society, as the country was a close ally of the Americans during this period. Coupled with issues of internal political instability, such “rifts” in society naturally translated themselves into the avant-garde works of Thai artists.

As a whole, ‘RIFTS’ makes for a thoughtful presentation. From the name of the exhibition, it may seem as if the curators are seeking to historicise this epoch of Thai art. Upon closer inspection, however, ‘RIFTS’ is an attempt to re-examine this “golden age” of contemporary art. This fluidity is encouraged by the notable absence of any art-historical theorising throughout the presentation, and is further augmented by a complementary section housing academic texts, archival materials and a comprehensive timeline. Instead of trying to narrate a particular point of view, the supplementary component acts as a jumping board rather than a finishing line and we, as the audience, are invited to make that leap.

Curated by Chol Janepraphaphan and Kasamaponn Saengsuratham, the exhibition presents 13 prominent contemporary artists such as Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Prasong Luemuang and Rirkrit Tiravanija. The works are sensibly chosen to showcase the wide range of modus operandi that blossomed during this period, be it in terms of the artists’ intentions or the execution of the works themselves.

Kamol Phaosavasdi, ‘Song for the Dead Art Exhibition’, 1985, mixed media, photography, video, document, sound, scrap metal, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Incisively setting the premise for the show, ‘RIFTS’ begins with Kamol Phaosavasdi’s ‘Song for the Dead Art Exhibition’ (1985), an assemblage of various components. Scattered like a whirlwind across the wall are texts on postmodernism, highlighting the artist’s rejection of modern art forms. This rejection expresses itself in the massive sculpture that Kamol has built out of scrap metal found objects. For many, the monstrosity that revels in its own anti-aesthetic self does not appeal to traditional ideas of art. Certainly, one can hardly consider a collage of scrap metal to be beautiful.

Yet it is this exact need for art to be conventionally attractive that the artist is interrogating and rejecting in the creation of this monument. Cleverly, the sculpture’s form suggests that it is “growing” out from the literal building bricks of postmodernism, as the text, ‘The Anti-Aesthetic’ edited by Hal Foster, is nestled within the bricks. As a starting piece, then, it provides the audience with a clear idea of the conceptual praxis that the showcased artists were embracing.

Kamol Phaosavasdi, ‘Song for the Dead Art Exhibition’, 1985, mixed media, photography, video, documents, sound, scrap metal, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Other elements in this presentation include multiple Marilyn Monroe images smeared with black paint and a panel espousing Jacques Derrida’s unpublished ‘The Postmodern Manifesto’. It is from the Manifesto that a sense of a new age dawning is made glaringly obvious, with maxims such as “The art of the past is past. What was true of art yesterday is false today”, and “Postmodern art is pastiche, parody, irony, ironic conflict and paradox.” In its totality, ‘Song for the Dead Art Exhibition’ is a defiance of modern art and a beacon towards a more self-reflexive and experimental mode of practising art. It is this “rift” in thinking and doing that deftly guides us as we make our way through the rest of the exhibition.

Pinaree Sanpitak, ‘Kiwi works I’, 1985, ‘Kiwi works II’, 1985, ‘Womanly Stroke’, 1998, ‘Solid as a rock’, 1990, ‘One of those nights’, 1991 (left-right), ‘The vessel / and everything in between’, 2002-2004 (centre), exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Not all works in ‘RIFTS’ are so declarative in their renouncement of tradition. This functions well for providing more diverse outlooks on the various paths that artists took in the shift from modern art to the contemporary, which seems to be the curatorial intention. Indeed, some took to exploring innovative artistic techniques to expand on the traditional norms of art-making.

A highlight of the show is an array of works created by Pinaree Sanpitak, and is one of the most varied collections for an artist in the exhibition. The selection provides a mini-historiography on how her practise has evolved, with the earliest work created in 1985 and the latest being 2004. With it, the audience get a quick glimpse of the kinds of concepts and techniques she has engaged with. While not extensive, since it is not a solo retrospective, it is nevertheless interesting to observe.

Her works are showcased in the same area as others who similarly explore the parametres of creating art. The experimental spirit of the artist is observed in how she weaves together various unconventional media to create a coherent and visually pleasing product. Take for instance how turmeric, pigment and charcoal are applied on Saa paper and canvas for ‘Womanly Stroke’ (1998), or how a collage of photographs, washi paper, and pastel come together for ‘Kiwi works I’ (1985).

Pinaree’s works also speak to social issues, which is a running theme in this exhibition. It highlights how practitioners were seeking to not only perfect their mastery over the technical aspects of art, but were also concerned with connecting their art to society. The curatorial framework of revealing confluences between art and socio-political trends shines through this aspect of the artworks. We see it in Pinaree’s ‘The vessel / and everything in between’ (2002-2004), where the artist presents an almost two metre-long container filled with water, fish and plants. The self-contained vessel acts as harmonious statement on femininity and womanhood via its metaphorical connotations of abundance and self-sustainability.

At the same time, ‘The vessel’ questions the limits of art and exhibition making. It is unusual to see live fish in a sanctified art institution, and this unexpected component is jolting and highlights just how unconventional the “rifts” were.

Michael Shaowanasai, ‘Exotic 101’, 1997, single-channel video installation, 7 mins, 5 stainless, dimensions variable, exhibition installation view. Image courtesy of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Closer to the end of the exhibition are artworks whose subject matters address Thailand explicitly. It is a fitting way to round off as this section provides a contextual linkage. After all, the showcase is meant for a largely Thai audience. To experience works that were, and continue to be, relatable to issues so close to home serves to reiterate contemporary art’s propensity for igniting conversation and change.

One such work is Michael Shaowanasai’s ‘Exotic 101’ (1997), which presents a video installation containing a satirical instruction film on how to pole dance, with the artist as the dancer. The film highlights the juxtaposition of Thailand’s highly religious society with strict sexual and gender norms against its ironically booming sex industry. The Thai body then becomes a battleground for the clash of values between the society’s normative standards, and the “exotic” body showcased for sex tourism. Accompanying this tongue-in-cheek critique are five pole-dancing platforms, emphasising the artist’s dark humour as they become supporting structures for exhibition-goers to rest on and contemplate.

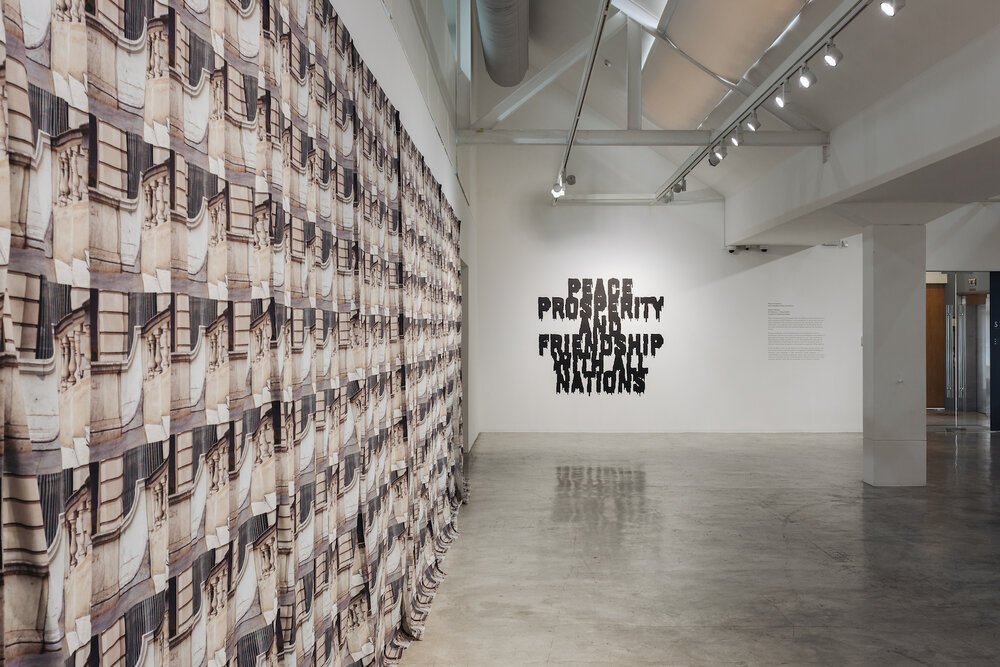

Installation view of archival materials. Image courtesy of Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Apart from the artworks themselves, a separate space is carved out for a reading area furnished with academic texts that provide a conceptual foundation, archival materials of pivotal moments for Thai art, and an impressively comprehensive timeline of global art-related events and significant Southeast Asian political, economical and social episodes from 1980 to the 2000s. It is a nice touch to this exhibition as it provides more context towards the cultural and historical significance of the works, rather than having the works exist in a vacuum. While there is a lack of strong signposting, like the seemingly random references on the timeline such as “Laos resumed a market economy approach” in 1986, the open-endedness may be intentional. It invites us to make connections within Thai art and how it relates to seemingly disparate events around the globe.

This open-endedness is reflected in the curation of the show as well. The exhibition is not presented in a strictly chronological manner, nor does the curatorial write-up and wall texts strive to be a history textbook. At the same time, the works are spatially configured to give us a good-enough flow without being overly didactic, beginning with the decision to start the show with ‘Song for the Dead Art Exhibition’, and the subsequent gentle groupings that emphasise on various aspects of the “rifts”, from experimental art-making to a focused emphasis on Thai society. It is this spirit of re-examination that prompts us to jumpstart our own explorations of the multiplicities of this period in Thai art. Such an analytical framework is useful for examining this exhibition, and by extension, for any grand narratives at large.

‘RIFTS: Thai contemporary artistic practices in transition, 1980s – 2000s’ is on view at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre till 24 November 2019.