A Review of 'Minimalism: Space. Light. Object.' in Singapore

The ambitious survey breaks new ground but only begins to scratch the surface

By Ian Tee

Haegue Yang, 'Sol LeWitt Upside Down – Double Modular Cube, Scaled Down 29 Times', 2017, aluminium venetian blinds, powder-coated aluminium hanging structure, steel wire rope, LED tubes and cable, 155 x 204 x 104 cm. Private collection, Taipei. © Haegue Yang, image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

'Minimalism: Space. Light. Object.' is the first survey of Minimalist art in Southeast Asia which also explores the movement's relationship to art in the region. The exhibition is organised by National Gallery Singapore (NGS) in collaboration with ArtScience Museum at Marina Bay Sands (ASM), with 150 works of art spanning both venues. As referenced in its title, the exhibition expands the ideas in Minimalism beyond its New-York-centric framework to include approaches in the American West Coast 'Light and Space' movement as well as notions of objecthood and immateriality.

This net is cast wide both in terms of its conceptual grounds as well as its attempt to map interconnected developments around the world. "The essence of what Minimalism is has always existed in Asia but their relationship has been very ambiguous," says Dr. Eugene Tan, Director of NGS. "We hope that this exhibition will help us reframe our understanding of Minimalism both historically as well as its legacies."

The exhibition takes place against a backdrop of fast rising market interest in Asia for artists like Hsiao Chin, Richard Lin and Nobuo Sekine, associated with Minimalist art movements such as Mono-ha and the Punto Art Movement.

'Minimalism: Light. Space. Object' at National Gallery Singapore, 2018, 'Minimalism in London' section gallery installation view showing works by Kim Lim and Rasheed Araeen. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

What this entails is also a reconsideration of overlooked artists who were part of a diaspora. The section titled 'Minimalism in London' contextualises Kim Lim and Rasheed Araeen within the dialogue of European formalist modernism. The artists were born in Singapore and Pakistan respectively, and both studied under the British sculptor Antony Caro. Lim's sculptures are influenced by her training as a printmaker at the Slade, often composed with a graphic flatness, while Araeen's background in engineering is evident in the works' attention to construction and references to architecture.

Roberto Chabet, 'Kite Traps', 1973, remade 2015, wood and rubber, 2 parts, each 183 x 92 cm. Collection of Carmen Mesina. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

The conversation between Southeast Asia and Euro-American Minimalism could at times be guided by formal connections without being relegated to superficiality. An example can be found in an elegant pairing of Roberto Chabet's 'Kite Traps' and Robert Morris's 'Untitled' felt piece from 1969, installed diagonally across each other. The works speak to relationships both in terms of colour and the use of soft materials which respond to stretch and the force of gravity. Notably, 'Kite Traps' was first shown in a 1973 exhibition Chabet dedicated to Postminimalist artist Eva Hesse, whose work is not represented in this survey.

Elmgreen & Dragset, 'Queer Bar/Powerless Structures, Fig. 21' (detail), 1998–2018, MDF, paint, beer taps, skirting boards, foot rests and bar stools, 150 x 300 x 300 cm. Haubrok Foundation. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

Another instance of a work from NGS's permanent exhibition being recontextualised to great effect is the dialogue between David Medalla's 'Cloud Canyon No. 24' from 1964 and 'Queer Bar/ Powerless Structures, Fig. 21' by the artist duo Elmgreen and Dragset. If the legacy of Minimalism lies in the enduring potential of its pure forms to take on new meanings, the explicit sexual politics in 'Queer Bar' might embolden a reading of queer undertones in Medalla's foam machines. The works are installed in the museum's public space outside the City Hall chamber. This public-private negotiation is a subtle move that should be made more explicit, perhaps in the guises of artwork descriptions or curator tours.

Po Po, 'Red Cube', 1986, oil on canvas, paper collage and gneiss, 218 x 154 x 50 cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. © Hla Oo and Po Po; image courtesy of Po Po and Yavuz Gallery.

Similarly, the section exploring the theme of Buddhism leaves more to be uncovered. Thai artist Montien Boonma's 'Nature's Breath: Arokhayasala' and 'Red Cube' by Po Po from Myanmar demonstrate how Southeast Asian artists combined forms associated with Minimalism with traditional practices. Yet, this is not to conflate such approaches with the hyperconscious reflexivity of Postminimalism. The evidence of an anomaly like 'Red Cube', which was developed in a country that experienced decades of isolation, still evades easy understanding and placement in art history.

Zhang Yu, 'Ink Feeding 20150506', 2018, plexiglas, Xuan paper, ink and water, 80 x 80 x 50 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Whereas its engagement with Eastern thought largely hinges on Gao Minglu's essay on Chinese Maximalism, represented by artists such as Zhang Yu and Tan Ping. The term proposes a reading of minimal form that deviates from Minimalism's cool reduction, rather privileging the act of making which is often charged with spirituality and culturally-specific meanings. A slight overlap occurs here between the curatorial direction across both venues, where the presentation of Mono-ha works might have benefitted being situated in ASM instead.

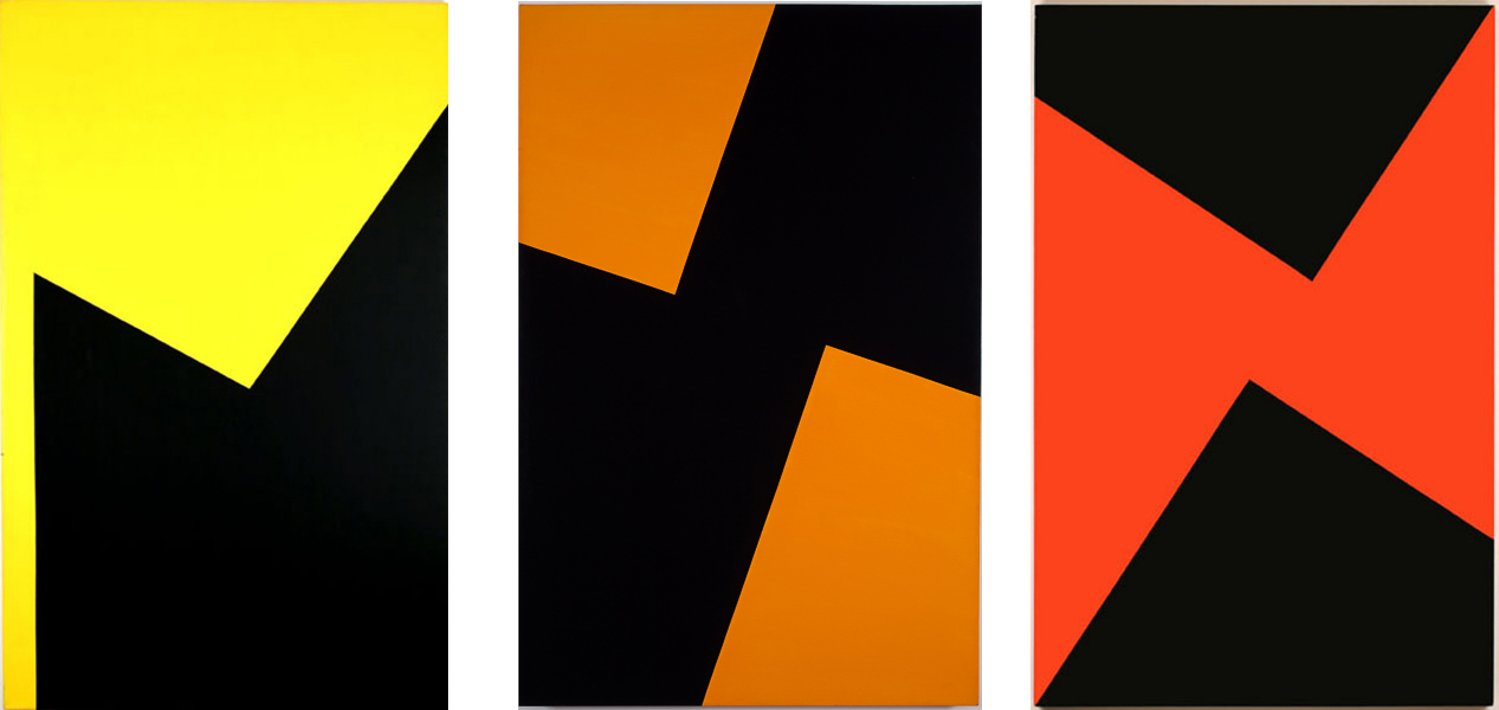

Carmen Herrera, 'Thursday', 'Friday' and 'Sunday' from the 'Days of the Week' series, 1975–1978, acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery.

While the effort to highlight influence of ideas such as Zen and I Ching in the formation western Minimalism is present, it is more successful in the examples of musical compositions chosen. One might think of names such as Agnes Martin, whose work neatly addresses this gap. More glaringly, the narratives presented in this survey continues to perpetuate male dominance despite broadened geographies. The story of women artists remains largely marginalised, accounting for roughly one fifth of the visual artists represented. Against this imbalance, works by Mona Hatoum, Haegue Yang and Simryn Gill still stood out, not least because they offer impactful encounters and new layers of discourse in such sprawling presentations.

This emphasis is not to reduce gender politics, or any form of representation, to a numbers game. Yet any critical discussion about Minimalism implicates a questioning of its mechanisms of privilege, more so in a type of art that is so self-referential it seems to efface any reference to its maker and context. The ambitious scope of 'Minimalism: Space. Light. Object.' inevitably resulted in loss of focus, though it does break the ground for more work to be done with its moments of inspiration, intrigue and insight.