Midpoint: Dinh Q. Lê

Career trajectories and generational shifts in Southeast Asian art

By Nadya Wang

We would like to introduce Midpoint, a new monthly series that invites established Southeast Asian contemporary artists to take stock of their career thus far, reflect upon generational shifts and consider advantages and challenges working in the present day. It is part of A&M Dialogues, and builds upon the popular Fresh Faces series.

Our first guest for Midpoint is Dinh Q. Lê, whom we spoke to at the National Gallery Singapore, where his work ‘Crossing the Farther Shore’ (2014) is part of ‘Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia’.

In this conversation, the artist speaks about moving his practice to Vietnam in the late 1990s, working with artists through Sàn Art in the past 15 years, and the stories – both old and new – that he wishes to tell.

Dinh Q. Lê with his work, ‘Crossing the Farther Shore’ (2014). Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

Could you share a decision and/or event that marked a significant turn/moment in your path as an artist?

It was probably in 1993, when I graduated from my masters degree and I was teaching. Before that, I applied for a grant to visit Vietnam, after 15 years of being away. And when I visited Vietnam with this grant, it solidified the decision for me to move back, or maybe not… I do not think I knew that I wanted to move back, but deep down inside, I did know it was the place I was supposed to be. I just didn't know how to move back. That was the thing. It was in 1997 that I moved back completely.

When have been milestone achievements for you as an artist, and why have they been particularly memorable?

When I was in America and studying art, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was always the dream because that is the high temple of culture in America, and I wanted to be part of it. When ‘The Farmers and the Helicopters’ (2006) were shown there for six months in 2011, I would say that was quite amazing. But then, like all goals, once you achieve them, there is another goal that you have to go after. But now, the goals are different. They are not biennales that I have to be in, or a museum that I have to be in, but more about making work that I can be proud of.

“But then, like all goals, once you achieve them, there is another goal that you have to go after. But now, the goals are different. They are not biennales that I have to be in, or a museum that I have to be in, but more about making work that I can be proud of.”

Could you walk us through a typical work day, or a typical week? What routine do you follow to nourish yourself/your artistic practice?

Usually I wake up around 9am or 10am, and I do a quick light breakfast and then go to the gym, which is a habit that I picked up because of the pandemic. Then I come back, have lunch and basically run whatever errands I need to. Sometimes, I set up meetings in the afternoon with artists or things that are related to Sàn Art. After dinner, I relax for a while, and at about 8pm, I go into the studio. Then I work until about 3am. So that is my schedule. I love that time because it is quiet, and there is nobody bothering me. Most of the time, I would purposely leave my phone upstairs and work through the night.

Could you describe your studio and how it has evolved over the years to become what it is today? What do you enjoy about it, and what do you wish to improve?

When I set up the studio in the house I built 20 years ago, I thought it was great. But now it is too small, because the work is getting bigger and bigger. So lately, I have been thinking about expanding the studio as I still have some land next to my house. The question is that it is going to take a year to build, and that is a lot to deal with in terms of the commitment. And I still have to focus and make work. Hopefully we can work on it sometime this year.

‘Masked Force’, 2020, exhibition view. Photo by Quang Dam. Image courtesy of Sàn Art.

‘Don’t Call it Art’, 2022 - 2023, exhibition view. Photo by Nguyen Hoai Ngan. Image courtesy of Sàn Art.

You have worked with young artists and curators through your involvement in Sàn Art. How did this agenda come about? Further, do you observe generational shifts in the Vietnamese art scene from this work? If so, what do you think are the causes/reasons?

When I moved back to Vietnam in the 1990s, there was not much of a contemporary art scene in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City). So artists, particularly young artists, were pretty much on their own and I was on my own. We needed a place to gather to meet each other, to support each other. So that is how Sàn Art came about, as a place to gather for us to talk to each other, but also a place for young artists to try out new ideas, to experiment and not worry so much about the commercial aspect of making art.

After 15 years, we are seeing about two different generations of artists that have come through Sàn Art. Many from the first generation now have big careers, which is great. They are artists such as Phan Thảo Nguyên and Trương Công Tùng who came to Sàn Art as students. And now Phan Thảo Nguyên just had a big exhibition with the Tate St Ives and Trương Công Tùng who was in the Carnegie International. So it is wonderful to see each generation start to build a name for themselves. And now we have another generation, who are younger than the Phan Thảo Nguyên and Trương Công Tùng generations. I hope Sàn Art will continue to be a place that they can come to for a long time.

For a long time, there has been a romanticised idea of who an artist is, and those from the older generation in Vietnam seem to make work when they feel like it. Meanwhile, artists from the younger generations take a more serious, professional approach. They are constantly working on ideas and producing work. Whether there's an exhibition or not, it does not matter. I think that is the key difference between the generations of artists in the country.

“We needed a place to gather to meet each other, to support each other. So that is how Sàn Art came about, as a place to gather for us to talk to each other, but also a place for young artists to try out new ideas, to experiment and not worry so much about the commercial aspect of making art. ”

What do you think were the unique advantages and disadvantages you had when you were an emerging artist, and with establishing your place since then?

I definitely had an advantage. I was already showing my works in America, and I could speak the English language, so I had built a network there. But today, more curators are coming to Vietnam. International curators, regional curators, and regional collectors are now very curious about Vietnamese contemporary art. So, that is their advantage. When I moved back to Vietnam, there was no curator coming in, and there was no collector looking for contemporary art. They came to buy traditional paintings, or the Indochine paintings. I had a unique advantage and the generation now has its own.

Dinh Q. Lê, ‘Crossing the Farther Shore’, 2014, found photographs, cotton thread, linen tape, steel rods, dimensions variable. Photo by Joseph Nair, West Memphis Pictures. Image courtesy of the artist and National Gallery Singapore.

Dinh Q. Lê in conversation with Roger Nelson. Image courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

What has become easier or more difficult to do as time has gone by?

I have become more critical of myself and that is more difficult in terms of making work. I am pushing myself with a higher standard and sometimes it is hard to even start a project. For ‘Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia’ it was Roger [Nelson] who reached out to me. He explained to me that the show was trying to document the history of photography practices in Southeast Asia. I was very happy and honoured to be included.

What do you think has been/is your purpose? How has it kept you going, or at times, how has it been challenging to push against boundaries in order to keep your focus? How has your purpose remained steadfast or evolved over the years?

Over the years, I try to bring out the stories that people have not heard of or thought of through my work. That has been the thing that has driven me, particularly about the Vietnam War. But now it is getting harder in a way, because I am asking whether this story is still relevant to the current generation. This story is from a particular time and a particular context, and they are changing. And so the question I am always asking myself is what my purpose is.

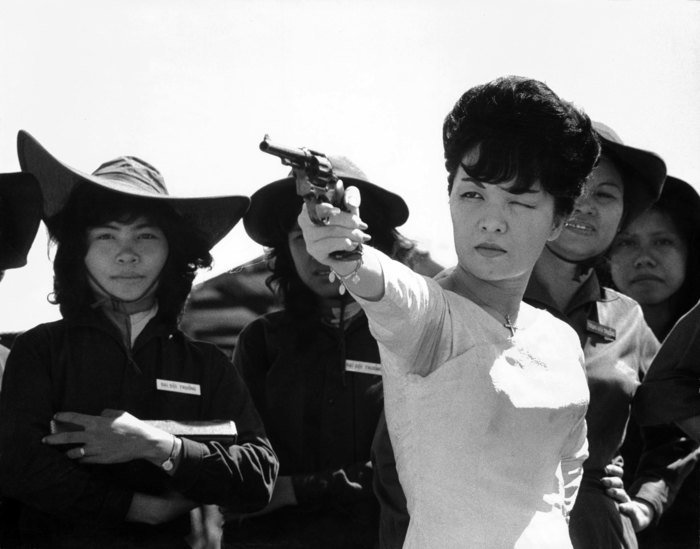

Photograph of Madam Nhu, provided by Dinh Q. Lê from his research.

Could you talk about current/upcoming projects?

I am still looking at some of the historical events in Vietnam. Right now, I'm looking at Madame Nhu. She was the sister-in-law to one of our former prime ministers, Ngô Đình Diệm, who was not married. She and her husband basically moved in with the prime minister, and she became the de facto First Lady.

She was so outspoken and in many ways, ahead of her time. I like her spirit, and I think in the context of today, we would look at her very differently as a strong woman. So that's where I am at the moment. But as I said before, it has become harder because I have been more and more critical of myself and so the project has been slower. But I've been researching for a couple of years now. Hopefully, I will try to start making work with it this year.

And finally, what would be a key piece of advice to young art practitioners? What has been your formula for success that they can learn from to apply to their own careers?

A long time ago, I moved back to Vietnam and a lot of people said, “What are you doing? You're committing a career suicide!” This was because in the 1990s, there was no art scene in Vietnam, and curators did not travel to Vietnam. But then the world changed and so did the region, and here I am. My advice to artists is to do what you want if it makes you happy. It doesn't matter where you are. Somebody will find you if you do something really interesting. Just be in the place that you want to be.

The interview was transcribed by Nabila Giovanna W, and has been edited.

“Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia” is on show at the National Gallery Singapore from 2 December 2022 to 20 August 2023. More information here.

Read other Midpoint series here.