Conversation with Artist-Curator Aung Myat Htay

Surveying Myanmar contemporary art

By Ian Tee

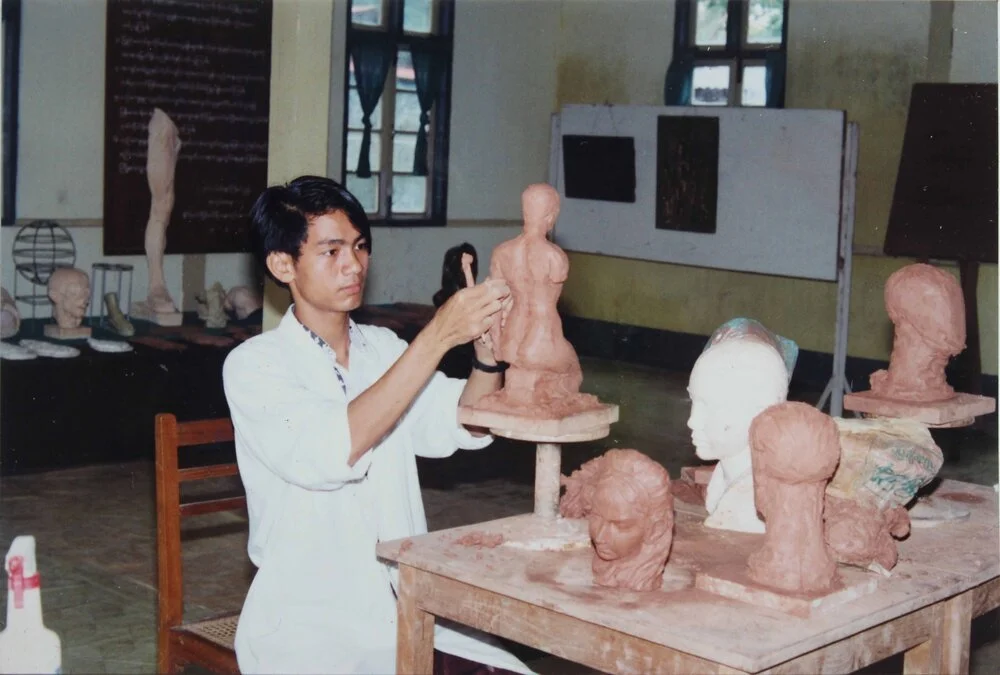

Aung Myat Htay.

The freedom of expression found in contemporary art is at the heart of Aung Myat Htay's practice. The Mandalay-born artist's outlook is deeply informed by the 8888 Nationwide Pro-Democracy Protests that swept across Myanmar during his formative student years. His work is steeped in symbolism, combining traditional forms and aesthetics with contemporary social commentary. Equally important are Aung's contributions as a curator and writer. His survey publications on Myanmar contemporary art are key resources in English that chronicle the evolution of creative expression from the country. He is also the co-founder of SOCA (School of Contemporary Art), an online programme focused on community-based and experimental art.

In this conversation, Aung shares his journey as an artist-curator and his observations on the development of Myanmar contemporary art.

Archival photo of Aung taken in 1995, during his first year as a sculpture student at the National University of Art and Culture, Yangon. Image courtesy of the artist.

Archival photo of Aung taken in 1998, at Swal Daw Pagoda Sculpture site in Yangon. Image courtesy of the artist.

You grew up working in bronze casting with your father and later studied sculpture at the National University of Art and Culture, Yangon. Could you talk about the art education you received in the late 1990s? How were you exposed to contemporary art?

I started my journey in art as a worker making traditional crafts. At that time, Myanmar was under the socialist dictatorship which closed its door to the outside world, so I did not have any knowledge of what was happening internationally. I enrolled at a State School of Fine Art in Mandalay in 1991 where I learnt painting skills and gained an interest in sculpture. I then moved to Yangon in 1995 to study at the University of Art and Culture, and graduated three years later with a Bachelor of Fine Art in Sculpture. I served as a tutor in the department of sculpture till 2001.

The university was opened by the military junta and art was taught in the model of 19th-century European academies. Even today, there is still no systematic study of modern and contemporary art history. The impact of the dictatorship remains entrenched in the system of the university, especially in its rejection of a global outlook in favour of patriotic, closed-minded policies. This is used to maintain traditional culture and emphasise "native" characteristics.

I feel fortunate that I got to participate in the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum's residency program in 2010. It was a pivotal experience that exposed me to what was happening outside of Myanmar.

Archival photo of Aung taken in 2010, at his residency studio in Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Japan. Image courtesy of the artist.

How did you keep your art practice going as a young artist after graduation? What were the exhibition opportunities available in the early 2000s? And did you have to take on additional jobs to make a living?

In the late 1990s, solo exhibitions were rare. Most of the gallery exhibitions were promotional group shows targeted at tourists, with little attention from local audiences. It was also hard to see modern art, unless you were in a diplomat's residence or office. However, outside of traditional exhibition spaces and galleries, some artists were doing experimental works and performance art.

It was, and continues to be, expensive to live in Yangon especially for aspiring artists. Costs were high because even if you had artworks, you still needed to rent an exhibition space or have a member position in a commercial gallery. I was able to do a solo show in 1997 before graduating and that opportunity came through support from my peers. On top of my job as a tutor at the university after graduating, I also did graphic design for magazines and a number of advertising agencies. Many artists end up working in the public sector or teaching at the faculty. I quit my job at the agency in 2010 after the Fukuoka Museum residency and became a freelance artist.

How did you end up doing curatorial research and work? Were there any peers or mentors who offered support and guidance?

I got into curatorial practice through writing art books after I left my job as a lecturer. My first book 'Basic Art Drawing' was published in 2002, and it was a useful reference for art students and amateurs. I later received more opportunities to write books related to art history and my experiences with art. I also got to meet international artists and scholars through seminars and events organised in cultural centres such as Alliance Française, Goethe Institute and the American Centre.

My first curatorial project came about in 2011, when I was invited to lead the Urban Reflection workshop at the New Zero Art space in Yangon. Another important early curatorial experience was being an observer at the Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS) Bard College in 2014, during my residency at Residency Unlimited (RU) Brooklyn.

Presentation at the Asian Cultural Council's office during Aung's residency in New York (2014). Image courtesy of the artist.

That six-month long residency in New York in 2014 was enabled by a grant from the Asian Cultural Council. What was your experience? And were there any insights that you brought back to Myanmar?

Receiving the Asian Cultural Council's fellowship Prize was a major turning point in my life, both personally and artistically. Through the grant and residency, I had the opportunity to experience the world of art in a very special way. It deepened my knowledge about curatorial methods as well as art movements such as Minimalism and Conceptualism. The CCS Bard programme and gallery visits in Manhattan were a shock and I had to deconstruct my practice. I broke from previous modes of working and started to find a new language.

At that time, it was a challenge to share the new ideas I encountered in New York. There was a gap in understanding as even modern art in Myanmar was focused on the craft of making. Contemporary art is rooted in experimentation and the exploration of social issues, so it is able to lead society in the creation of new cultures. I also needed time to reflect on the experience and my own identity.

DVD magazines curated by Aung Myat Htay: 'An Introduction to Contemporary Art in Myanmar' (2013) and 'Silence is Golden' (2019).

Two important projects you curated are 'An Introduction to Contemporary Art in Myanmar' (2013) and 'Silence is Golden: Myanmar Art After Political Changes' (2019). Both are publications that survey artists across generations and working in different media. Was it a conscious decision to have a different group of artists in each project? Do you observe any trends, shared concerns or approaches used across both sets of artists?

Both programmes use a documentary template for surveying contemporary art in the country. The idea came from a video programme I watched during my residency in Bangalore, India, in 2011. It was created by a Swiss curator, and I found this interview format to be the best way to consolidate and spread information about artists in Myanmar. Even though there were many art exhibitions and events happening in the community then, these activities weren't publicised or archived by the media. The first volume was released in 2013 with the help of artist friends, while I received support from Aura Mekong Contemporary Art Project for the second volume. They helped to produce the catalogue and circulate the publication to regional networks.

Yes, it is true that I wanted to highlight a different group of artists in each publication, even though some from the first volume had new works and were worth featuring again. The first project had an introduction based on medium, followed by a list of artists. In the second, each artist's vision was contextualised within Myanmar's political landscape. I wanted to account for Myanmar's relative "silence" in the region and bring out the differences across generations. I hope that by explaining the current situation, we can work towards socio-political reform and imagine the future.

Aung Myat Htay, 'Illusion Faces', 2012, installation and workshop at New Zero Art Space. Image courtesy of the artist.

Speaking about artist collectives and spaces, Myanmar's first artist collective, Gangaw Village Group, was established in 1979. Aung Myint and some of Gangaw Village members started Inya Gallery in 1989, which was one of the few alternative art spaces for contemporary practices. A more recent example might be Aye Ko and the New Zero Art Space.

Are there local artist groups and spaces that excite you today? In what ways are they connected to these groups that came before?

Due to Myanmar's political history, we do not have strong artist collective movements. While there were groups organised informally around friendships, these communities were not unified. Art practices taught in the institutions espoused the expression of private feelings, so artists tended to live and work separately. However outside of the academy and government institutions, students found ways to rise up against constraints imposed by the military regime. The Gangaw Village was an independent group started by students who worked in the modern art style, and included architects, film makers and illustrators. Other groups who were also active in Yangon in the last few decades include Rectangular lantern, Wild Eyes and New Zero.

The art scene in Myanmar today remains dominated by these established groups and the modern art trend is still alive; but things are also changing. Young graduates are experimenting with new concepts and working in their own style in film, music video and poetry. Noise in Yangon, Thuma Collective, Dawei Art Space, 3-ACT and Pyinsa Rasa are interesting, enthusiastic groups finding their own way in the absence of government support for the arts.

Aung Myat Htay, 'Are We in a Fail State', 2018, textile, light, dimensions variable, installation view at SOCA Space. Image courtesy of SOCA Space.

SOCA (School of Contemporary Art) is an online learning programme you initiated in 2015 as a response to the lack of resources on contemporary art in Myanmar. Could you talk about the content available in SOCA and the audience it is meant for? And what function does SOCA space serve?

The SOCA programme is based on developments in contemporary art. It doesn't operate like a school in the traditional sense, but rather, is an online project for young people to learn about recent trends. I realised that they are less willing to engage with new forms of art because they think they do not have the experience and skills to do so. There is also a general lack of exposure to challenging material and ideas in Myanmar. Through hosting workshops and other events, SOCA aims to be an educational platform for the younger generation and create more opportunities for experimental practices.

In 2018, we rented a room for SOCA Space and hosted exhibitions, workshops and talk events there. The physical space was closed in 2019 due to budget constraints, but we continue to be active digitally. SOCA's latest online programme 'The Way We Live' deals with media art in the time of social distancing.

Are your curatorial work and personal artistic practice connected? What are the challenges or problems you faced managing both roles?

I understand curatorial work as a part of the artistic journey. There is a need to organise artworks in meaningful ways, and I think of these concepts as the curator's art form. Of course, there are responsibilities tied to this role.

Personally, it is difficult to assign time for both roles and this inevitably affects artistic practice. For instance, I produce fewer artworks now. That said, through my curatorial work I've come to realise things that weaken our professionalism, such as the lack of art management systems. The solutions might not be formal arrangements but I just wish to pose this challenge.

Aung Myat Htay, 'A Book of Institution Republic of the Union of Artopia' (detail), 2019, marble, 29.2 x 20.8 cm (each). Image courtesy of the artist.

Your latest performance 'A Book of Institution Republic of the Union of Artopia, 2019' involves adding the audience's blood onto carved marble tablets. Could you talk about the idea behind this work?

The work was performed at the opening of my exhibition 'Consciousness of Realities' (2019) at Myanm/art in Yangon. It was the third in a series of three chapters: the first was presented in an open studio in New York, the second was in 'The Segments' solo in (2016) at Myanm/art. The title 'A Book of Institution Republic of the Union of Artopia' refers to the 2008 Constitution of Myanmar, which instituted laws that protect unfair discrimination. Just like those laws, self-censorship also plays a key role in perpetuating the status quo.

In the work, marble tablets are in the shape of books with a carved, mixed-species beetle. It is an animal associated with the apocalypse and destruction of nature, thus also symbolising the self-serving ego, a theme of the exhibition. It speaks to the superstitions in Myanmar and predatory rulers who create policies that feed ruthlessly on the citizens' blood.

Aung Myat Htay and Myanm/art founder Natalie Johnston at the opening of his exhibition 'Consciousness of Realities' (2019). Image courtesy of Myanm/art.

In your essay 'Changes and Uncertainties in Contemporary Myanmar Art' (2017), you brought up several issues hindering the development of the Myanmar contemporary art, such as the lack of professional curators as well as divisions between artists who studied locally and abroad. What are your thoughts on the situation since the essay’s publication?

Currently, there are only a few scholars in the art scene who have international exposure. However, the ones who graduated abroad are pushed out of the official system and aren't in the position to make necessary changes. Art and culture are not priorities for the government when there are issues such as corruption, social problems and class conflict.

Is development in arts slow due to the lack of government support? I don't think it is needed for new art to emerge, but I do worry about the state of art and culture in Myanmar. The former dictatorship entrenched attitudes that still control institutions and systems today. There is a chance for this situation to be reversed and I believe academics need a role to play in this resistance for creative freedom.

The essay also discusses the role of international organisations in the Myanmar art scene, and ends with a message for local artists: "… artists need to make wise decisions by weighing up their options. They need to examine who is benefitting and how. They also need to work to change the policies regarding art and culture."

International organisations have been supporting the development of Myanmar's art and culture for decades, and I want to acknowledge their active contributions. In the statement you quoted, my intention was to emphasise the need to reflect on the standards of local art events. We need to put more consideration into curatorial ideas and how they are communicated. Adding an educational component will also benefit the future creative community.

Another thing to be aware of is the weakness of Myanmar's cultural policy, which prevents "outside" culture and ideas from entering the country. Hence, it is difficult to organise international exchange programmes. The current regime is plagued by the burden of past dictatorships and that has a big impact on the way external art organisations work with government institutions. Fixing these issues will bring a new era for Myanmar contemporary art.